Culture affects how employees relate to

each other; how they view the organisation; and how they go about their work.

It is therefore critical that organisational culture and practices be aligned

to the cultural values in the societies in which they operate.

ABC Limited operates across several

countries and is therefore bound to be affected by cultural differences in the

different countries. These differences can easily be explained by focussing on

the five cultural dimensions highlighted by Hofstede which include uncertainty

avoidance, individualism, power distance, masculinity and long term/ short term

orientation.

This report finds that it is necessary

that the cultural differences be taken into account in modifying the business

practices to ensure productivity is maximised at the subsidiary levels. This

move is expected to give rise to complications where teething problems could arise

in understanding how different subsidiaries work and how to relate with others

in different countries.

Among the remedies recommended for

resolving such issues are: undertaking trainings on cultural differences and

corresponding differences in business practice; provision of guidelines for

quick reference; strategic alignment of the different functions across

countries; and the rotation of staff to different countries.

Culture affects all facets of life as it

affects how individuals view themselves as well as how they view each other

(Tung and Verbeke, 2010). It guides the manner in which people relate to each

other and also how they perceive various messages and communications from

others. This impacts business practice in terms of work organisation,

relationships between workers and between the workers and their superiors, the

organisational culture, motivation schemes and other facets. Some of the

cultural dimensions that impact business practice include the power distance,

the level of individualism, the level of masculinity, type of orientation and

the uncertainty avoidance index (Hiroko, 2009).

ABC Limited is a UK

company that wishes to increase its level of involvement in the Chinese and

Indian markets. This comes with certain implications in that differences in

cultural perspectives are expected to surface and possibly inhibit the

effectiveness with which the organisational goals can be achieved.

Consideration of cultural differences is crucial in organisations operating

across different cultures. This paper

evaluates the cultural differences between the UK, India and China and

evaluates how they are likely to impact business practice. It then makes

recommendations on the best approaches for ABC Limited to take to ensure that

its cooperation with Indian and Chinese engineers produces the desired results.

According to the recommendations of

Geert Hofstede, there are five important cultural dimensions that could be used

to distinguish cultures across various countries. These dimensions include

power distance, uncertainty avoidance, long term versus short term orientation,

masculinity versus femininity, and individualism versus collectivism (Hofstede,

2012).

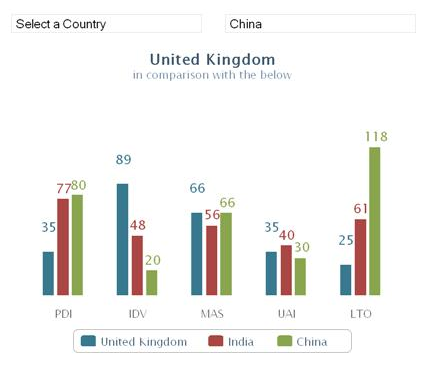

Source:

http://geert-hofstede.com/united-kingdom.html

This dimension refers to the extent to

which members of a population are comfortable with the fact that power is

distributed unevenly between different members of the society. Where power

distance is low, it means that the inequality in power is generally

unacceptable and those wielding power often required put under pressure to

account for such inequalities (Newman and Kollen, 1996). Organisations

operating in areas where the power distance is high tend to do well where

hierarchical models are adopted. The power distance index in the UK stands at

35 as compared to India’s 77 and China’s 80 (Hofstede, 2012). This means that

the hierarchical order is more acceptable in India and China than it is in the

UK.

Individualism refers to a situation

where members of a society are expected to be only responsible for themselves

and members of their immediate families. People are primarily seen as

individuals. In the collectivist perspective, people are seen as members of

groups who are expected to work towards the achievement of group objectives and

conduct themselves in a manner that reflects on the ideals of such groups

(Laroche, 2011). A comparison of the individualism index between the country

cultures under consideration places the UK at 89 followed by India and China

with 48 and 20 respectively (Hofstede, 2012). This means that China is a

strongly collectivist culture with the UK having a strongly individualist

culture.

A culture is said to be masculine when

it is dominated by the desire to be heroic and characterised by the search for

material reward for success. It emphasises competition and assertiveness.

Femininity on the other hand is characterised by cooperation, modesty and the

desire to take good care of the weak and is generally oriented towards the

building of consensus around pertinent issues (Suku and Nishal, 2007). The

masculinity index for UK, India and China stands at 66, 56, and 66 respectively

(Hofstede, 2012). In other words, there aren’t major cultural differences as

far as this dimension is concerned.

This

dimension describes the extent to which people are uncomfortable with ambiguity

(Jameson, 2007). This denotes the need to define processes in a manner that

ensures that all procedures are documented accordingly. Where the index is high,

operational procedures are held high. On the other hand, societies with a low

uncertainty avoidance index emphasise the importance of maintaining the overall

principles while paying little attention to the specific procedures to be

followed. Among the three cultures under consideration, the uncertainty

avoidance is highest in India with 40, followed by UK and China with 35 and 30

respectively (Hofstede, 2012).

This dimension deals with the search for

virtue by societies. Short term oriented societies emphasise on absolute

adherence to culture and achievement of quick results (Pranee, 2009). They also

tend to be less thrifty and will in many cases focus on attaining the highest

level of satisfaction in the shortest time possible. In the long term oriented

societies, focus is more on long term results where societies believe in saving

and thriftiness in their expenditure. Cultural aspects such as truth are not

greatly emphasised as cultural realities are bound to shift with time. The long

term orientation indexes for the UK, India and China are 25, 61 and 118

respectively (Hofstede, 2012).

It is important to understand that

business organisations are part and parcel of the societies and that they are

bound to be affected by the cultural values in their host countries. Numerous

studies have been conducted to establish the importance of aligning business

practices to cultural contexts with evidence strongly pointing towards the fact

that such alignments are necessary for survival (Kanungo, 2006). The dilemma

between the need to pursue a globalisation strategy and localisation strategy

comes to the fore with the advantage of the former being that the uniformity of

operations around different countries helps in ensuring the ease of reporting

and quality control. It also lessens the risk associated with the delegation of

too much power to country managers where wrong decisions could result in grave

consequences for the organisations. Analysts however view such advantages are

dismal as compared to the benefits associated with the adaptation of a

localisation approach (Tcharchar and Davis, 2005). This approach emphasises

country culture and unique characteristics that are considered as crucial

towards ensuring that the organisation runs successfully.

Employee productivity

which is closely related to the level of motivation among such employees is

known to rise when the business practices are in line with their cultural

orientations. The understanding of cultural differences helps in estimating the

impact of certain changes and the conducting of the cost benefit analysis

(Leung, et al., 2005). Where cultural differences are slight, there may be

little or no need to alter business practices. For instance, business practices

that would be directly impacted by the masculinity dimensions in the three

countries under consideration may not need to be altered since the differences

are only slight. However, where the dimensions such as Individualism and Long

term orientation are concerned, it becomes absolutely necessary that the

organisational practices affecting them be aligned accordingly (Randall, 1998).

It is important to focus on Hofstede’s dimensions of culture when focussing on

the implications of culture on business practice.

The impact of the power distance on

business practice affects the approach to leadership and the level of formality

within the organisations. The power distance in China and India are relatively

higher than in the UK and this calls for the establishment of a business model

that affects such a reality. Businesses in the UK tend to encourage for

casualness in the work place where employees see each other as colleagues and

comparatively equal partners in the delivery of organisational objectives

(Hiroko, 2009). On the other hand, it is expected that in the typical

organisation in China and India, a higher level of formality is practiced.

Seniors should be addressed with their titles at all times in appreciation of

their status. Similarly, the leadership style would tend to be more

authoritative with subordinates taking the view that the leaders should be the

ones to dictate how the organisation conducts its business (Hiroko, 2009). This

is different from the UK approach where democratic leadership tends to be more

common than other models.

This dimension affects the manner in

which work is organised and is largely associated with the approaches taken in

relation to human resource management. When translated into the business

context, cultural perspectives on individualism determine whether employees are

more effective when working as individuals or if they prefer to work in groups.

In strongly individualistic countries such as the UK, work organisation

emphasises on the responsibilities of the individual (Tung and Verbeke, 2010).

Similarly, reward schemes are mainly individual-based with employees often seen

as competitors seeking to out do each other and achieve the greatest merit. In

a collectivist context such as China, employees work best in teams where groups

are given goals to deliver. They thereafter allocate specific duties to each

other and are accountable to each other. All efforts are channelled towards

delivering on the group objectives. Where the preference for collectivism isn’t

very strong, a mixed approach could be taken where groups are assigned duties

but with provisions for recognising and awarding the group members that

contribute the most towards the success of such groups (Laroche, 2011). Such an

approach encourages group members to do their best despite the fact that their

efforts are simply meant to contribute to the success of their groups.

As has been mentioned above, there are

no significant differences among the countries under consideration as far as

masculinity is concerned. However, it is important to take note of the

underlying cultural values that could impact this cultural dimension. It is

expected that even though the masculinity indexes for China and Britain are

equal, the fact that China is strongly collectivist would see less emphasis on

competition between employees. The existence of cut throat competition among

employees can be detrimental to business especially where employees fail to

cooperate with each other in fear of the credit for achievements being taken by

others (Kanungo, 2006). A balance must be struck and this delicate balancing

should be done in a manner that ensures optimum productivity in the

organisations.

This cultural dimension often affects

the need to define authority limits and the need to introduce procedural

guidelines in business practice. It may also denote the level of trust given to

supervisors and managers where low levels of trust are synonymous with strict

controls and limits over the managers’ ability to alter standing procedures

(Jameson, 2007). Similarly, reporting lines, working schedules and normal

operations may need to be fixed depending on the level of uncertainty avoidance

in the society. A business in India would therefore need more precise

guidelines than one in the UK or China. In the context of ABC Ltd, it would be

expected that the Chinese engineers would be furnished with the overall plans

and left to figure out how to deliver on the goals while their Indian

counterparts would do better with precise instructions on what to do and what

not to do.

In business, the long term orientation

impacts the manner in which short term performance is viewed. Where a society

embraces the long term orientation, emphasis is on the long term outcome and

temporary setbacks are not taken as a cause to worry (Pranee, 2009). There’s

little emphasis on specific procedures in view of the fact that their importance

is only relative and not absolute. Persons under this culture are therefore

likely to ignore specified procedures and rules where they believe that the

overall goal is not jeopardised. For instance, in the construction of an

engineering design, a firm with a low long term orientation would emphasise on

the need to achieve certain periodic milestones with the absence of such

achievements often able to trigger panic over the viability of the entire

project. On the other hand, a long term oriented organisation would take such

set backs as only temporary and not necessarily able to jeopardise the entire

project.

In the context of an organisation such

as ABC Ltd whose activities span across different cultures, it is imperative

that areas of conflict between employees in different countries are identified

and pre-emptive measures taken to ensure that operations are smooth. The first

step should be to make a decision on whether to localise business practices in

the countries in question or to impose the global practices. It is recommended

that a localisation strategy would work best for the company.

The extent to which

localisation is done should be dependent on necessity as well as the cost and

benefit of the same (Hiroko, 2009). Slight cultural differences do not warrant

any modification of practices. However, it would be necessary to consider

modification in areas where cultural differences are significant. For instance,

business practices that would normally be affected by dimensions such as

Individualism, power distance, and long term orientation should be localised.

Localisation is

expected to generate problems especially where operational cooperation is

needed across the three countries. For instance, confusion may arise where an

individual in the UK is responsible for a dimension and has to work with a

group (not an individual) in China. Issues of procedure may also cause

confusion where there’s little emphasis on short term objectives. In view of

the fact that complete localisation may be counterproductive, it is important

that such moves be made only where it is necessary. In many cases, procedures

can be replicated across the globe albeit with slight modifications. The cases

where significant changes are made should be clear and easily understood. This

would call for training of all the persons to be involved. Engineers expected

to work closely with their Indian and Chinese counterparts need to be taken

through training where perspectives in each of the three countries are brought

forward. Simulations of problems likely to arise should be created and

demonstrations made on how such problems can be resolved amicably.

Periodic rotation of

key personnel across countries can also work well in ensuring that

understanding is fostered across cultural borders. When employees experience

the perceptions and operations in the different countries, they are better equipped

to know how to relate to each other and how their differences can be countered

to ensure the achievement of the overall goals.

Hiroko, N., 2009. How unique is Japanese culture? A

critical review of the discourse in intercultural communication literature. Journal of International Education in

Business. 1(2), pp. 2-14

Hofstede, G., 2012. National Culture Comparisons. (Online) Available at:

http://geert-hofstede.com/united-kingdom.html (Accessed 22 April 2012)

Jameson, D., 2007. Reconceptualising cultural

identity and its role in intercultural business communication. Journal of Business Communication, 44,

pp. 199-238

Kanungo, R.P., 2006. Cross culture and business

practice: are they coterminous or cross verging? Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 13(1), pp.

23-31

Laroche, M., 2011. Globalisation, culture and

marketing strategy: introduction to the special issue. Journal of Business Research, 64(9), pp. 931-933

Leung, K., et al., 2005. Culture and international

business: recent advances and their implications for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36,

pp. 357-378

Newman, K., Nollen, S.D., 1996. Culture and

congruence: the fit between management practices and national culture. Journal of International Business Studies, 27,

pp. 753-779

Pranee, C., 2009. Impact of Chinese cultural

development and negotiation strategies, FDI, competitiveness, china

international business growth and management practice. International Journal of Organisational Innovation, 2(1), pp. 13-4

Randall, R.N., 1998. Understanding compensation

practice variations across firms: the impact of national culture. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(2),

pp. 87-99

Suku, B., Nishal, S., 2007. National culture,

business culture and management practices: consequential relationships? Cross Cultural Management: An International

Journal, 14(1), pp. 54-67

Tcharchar, J.D., Davis, M.M., 2005. The impact of

culture on technology and Business: an interdisciplinary, experiential course

paradigm. Journal of Management

Education, 29(5), pp. 738-757

Tung, R.L., Verbeke, A., 2010. Beyond Hofstede and

the Globe: improving the quality of cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies. 41,

pp. 1259-1274

No comments:

Post a Comment